There is a lot of writing advice out there. Some might say too much.

But this newsletter post from James Horton, Ph.D., was truly some of the best writing about writing I’ve seen in a long time.

It’s mostly geared toward the concept of writing more or becoming a prolific writer. Unsurprisingly, it’s a mental challenge more than anything, but he offers some genuinely interesting and useful things to try that feel much better than vague encouragement to just do it.

He describes his non-writer’s preconditions for writing:

Writing should be worthwhile. Since writing is a high-cost activity we decide it should only be used on high-reward projects.

Writing should be done once. Since writing is a struggle there’s diminishing value to doing anything that isn’t the project.

Writing should be done right. Further, since writing is a struggle, there’s no reason to circle back to edit it and make it better. One and done. Who in their right mind would sign up for a second beating?

Honestly, this resonates pretty well with me, even as various day jobs have required me to be a writer, without the benefit of time to be so perpetually blocked and unmotivated in my personal projects.

My favorite bits from his suggestions to fight each one of these:

Writing should be worthwhile

Counterpoint: No, it shouldn’t. He describes how the writing that’s accessible to the public is only a fraction of the writing he does. The rest he calls “dirt.”

“Dirt” doesn’t mean bad compositions. It means most of my writing is not composition. It’s random thoughts, or notes to myself, or explorations into my interests. My rule is to listen to my brain — if it wants to write nothing but to-do lists for two weeks, I listen to it.

His reasoning is really what makes it land:

Why? Well, you need dirt to grow plants. A farmer I admire once wrote that 90% of his job was dirt management. Manage the dirt well and the plants grow themselves.

He offers two suggestions for writing one can do of this kind, and I’m particularly obsessed with one of them: meta-writing.

This is simply “any writing that externalizes my thoughts so that I can sift through them.”

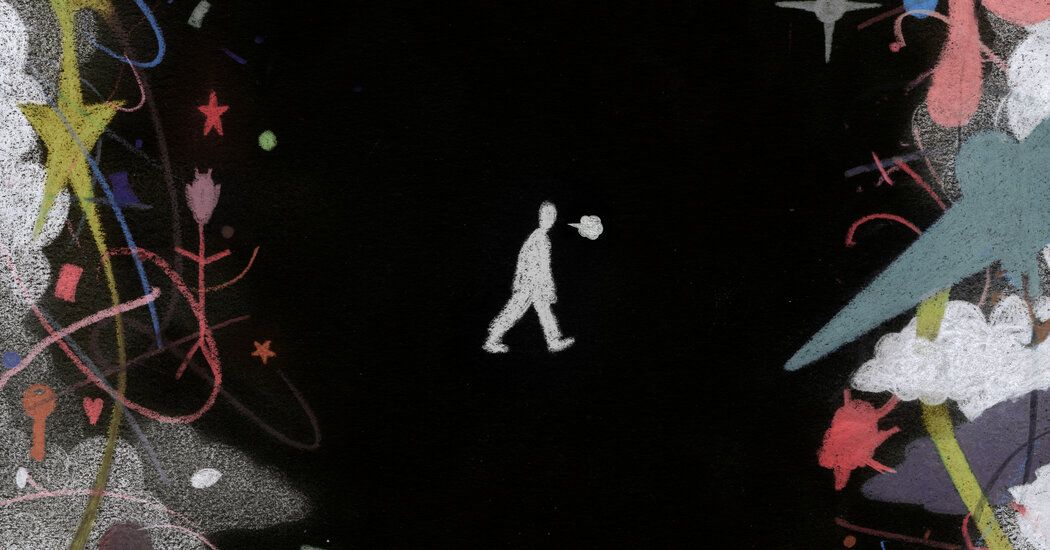

My first thought went to a New York magazine piece by Adam Moss that gave a behind-the-scenes look at Jonathan Franzen’s process while writing The Corrections. The piece centers on a journal Franzen kept while writing the book, and it’s full of excerpts that are essentially letters to himself about what he’s feeling about the day of writing he’s just done. I remember reading that and thinking 1) what a great idea it is but 2) how much extra writing it must have felt like.

But to view of it in light of Horton’s advice, it’s easy to see how this could have been some of the most valuable writing Franzen was doing at the time. I also remember thinking, “Wow, that’s just the level of dedication he had as a writer.”

But again, hearing Horton’s version, it feels less like dedication and more like a necessary part of a healthy writing process. It’s not really “extra” writing; it’s more integral than that by virtue of its capacity to offload and externalize the countless thoughts that must be racing through a writer’s head in a big project. It’s such an easy and approachable way to do more writing in the first place, to build up the muscle, and to perhaps learn something about yourself in the process, ultimately leading to something worth writing about.

Writing should be done once

Counterpoint: No, it shouldn’t. It’s a process. Always has been. Hemingway didn’t advocate just writing while drunk; it had to be followed by editing while sober. And there’s an old saying I’m constantly telling my students: Good writing is just rewriting.

He calls it a “splat draft” — the sound everything makes when simply thrown at the page. Anne Lamott famously called it a shitty first draft. Same concept. Put everything down on the page and wipe away that which does not suit you. Not sure why it’s so hard for me to do, other than not trusting that it’s a process. I fall prey to this one all the time, and it’s an easy fix.

Writing should be done right

Counterpoint: No, it shouldn’t. Closely related to the splat draft, when you think about it. Horton writes:

The key to overcoming this precondition is to force yourself to write incorrectly. This doesn’t mean abandoning quality: it means turning quality into its own step, separate from composition.

What a simple concept. They’re not the same thing, and his point is simply to practice separating them in your mind. Get comfortable writing things that you know you’ll have to clean up later. When you know you’ll have to do it anyway, you can free yourself up to write what you really want to be writing.