Since You've Been Gone

I remember my dad, plus some news stories that reminded me of him, what phones do to our reading lives, O.J. Simpson, marathons, and more.

Yesterday marked a year since I lost my dad.

What a strange sentence that is to say. Still. After a year of practice saying the last part—the most important part “I lost my dad”—it still doesn’t feel real.

I think of all the things I’d want to tell him, of what he’d missed over the past 365 days.

I’d tell him painful truths, about how my chest hurt for weeks after he passed and how long I’d stayed in Selmer after he was gone. I’d tell him small and unremarkable things, like how much fun Stuart and I had at the FedEx St. Jude Classic in August last year and can’t wait to do it again. I’d tell him about all the food and drinks and experiences we had on Stuart’s bachelor trip. I’d tell him about how we went to see Jerry Seinfeld as a family, and how it was that night that started us on our current path, with his beloved getting a phone call at dinner just before the show that would lead to a cancer diagnosis of her own. I’d tell him about how handsome his baby boy looked on his wedding day, how gorgeous his new daughter-in-law looked, and how much he was missed at that ceremony and party. I’d tell him how his granddaughter has grown, but she still recognizes his picture not just as “Papaw” but “That’s Papaw at my birthday party.”

It’s one of my great regrets that he wasn’t here after my trip to South Africa. That trip was filled with stories that he would have loved. It’s one of the most lasting memories that when he first met Courtney, he was so curious about her home country. He asked her countless questions and loved hearing her talk. He would have loved the photos we took while we were down there.

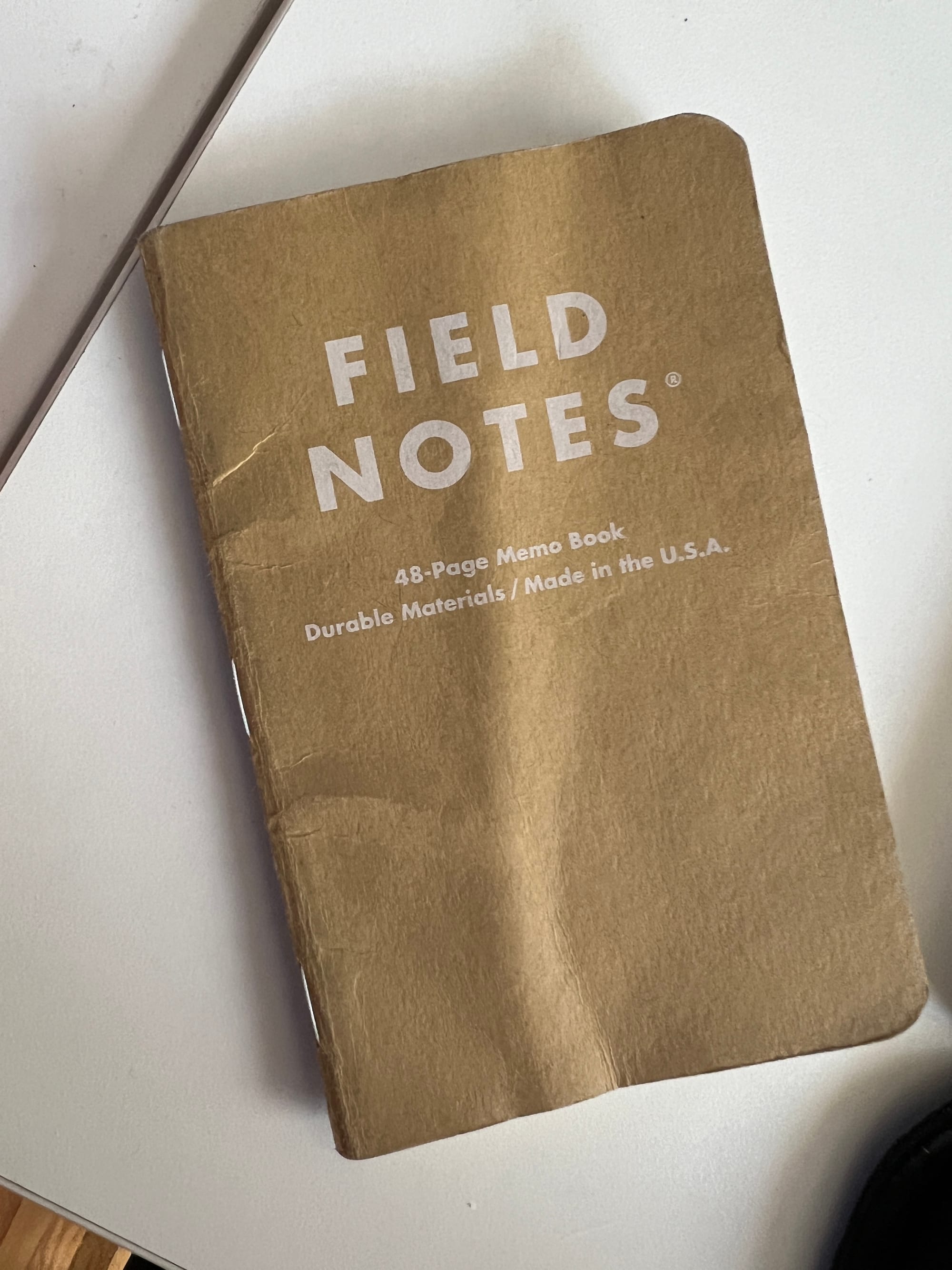

There was lots more that happened in the past year, and I’ve been taking very seriously the practice of journaling and writing down all sorts of things in notebooks. I wrote just a week ago about how I loved a new podcast where John Dickerson reflected on 30 years’ worth of notebooks and loved how a single notebook might contain “his thoughts about life, parenthood, death, friendship, writing, God, to-do lists, and more,” all in a single notebook.

That wasn’t the case with this notebook.

This was the new notebook I had in my back pocket when I traveled home for what would be his final days. Its first entry was his eulogy. After that, nothing felt quite right alongside those words. Eventually, I thought a nice bookend would be a speech for my brother’s wedding, and therein would be a time-capsule of both the extreme lows and highs of 2023.

I hadn’t looked back at those words since then. I don’t remember saying them, and I only barely remember the act of sitting up late at night to write them down, certainly not the ideas or the content of what I wrote. But this had some memories that I’d forgotten I’d highlighted, and when I really think about what I’d tell my dad if I had the chance, it’s some of these things and what they meant to me. If I’d been stronger, I might have said some of it after we learned we would lose him. But I wasn’t. The best I could do was to stand up in front of a room full of people, on a Monday just like today, and wish he were in the audience.

I worry about this eulogy, and I’ll tell you why: I am my father’s son.

Not really knowing what to say that could possibly sum up my 35 years of knowing Randy Littlejohn, let alone his 66 years and 10 months, raises the possibility of rambling. Anyone who knew my dad knows he was a talker.

I remember a story Mom used to tell from when I played baseball in high school. Another parent asked her all serious-like: "Is everything OK with you and Randy?"

Mom said “Yeahhhhhhh…why?”

The woman said, “Well you just drive separately to the games and never sit together.”

Mom just kind of laughed and waved a dismissive hand and said, “Have you ever tried to watch a ball game with Randy? He’ll talk the horns off a billy goat.”

I’m afraid I’ve inherited that same trait. But cutting against that is the overwhelming urge to cry. To guard against that I’ve tried to keep it short, and if I can’t fight the urge, then it might be very short indeed.

To keep it short is to keep it simple, which fits him well. That’s not to say he was simple—he was a man of action and hobbies which at various times included flying lessons, horseback riding, golf, martial arts, rock climbing, woodworking, drawing and watercolors, hunting, fishing, hiking, and others. He was a complex and interesting man.

But “simple” fits him because he did the simple things well. By that I mostly mean he was always there.

He was always there for his wife of nearly 44 years, in good times and bad, for richer and poorer, till death did them part.

He was there for his country, when he served in the United States Marine Corps in the 1970s.

He was there for his TVA coworkers, helping crews across the Mid-South for two decades.

But what I can talk about most clearly are the ways he was there for his kids.

He was there when I took the wing of a Batman toy because it looked like the boomerang weapon he’d use on bad guys, but when I thew it, wouldn’t you know it hit a wrought iron railing and knocked it loose? At least I swore that’s what happened.

Except he watched me from the window walk over and kick out that railing after repeated attempts.

As a result, he was there for the only real whipping I ever got as a kid (and for once I wouldn’t have minded if he’d missed a day or two).

He was there by side in a flash the time I was helping him put up a sign, and as I held it to the brick wall from atop the ladder, a big gust of wind got between the wall and sign and off the top of that ladder I tumbled. I’d never seen him move so fast, jumping off his own to tend to my injuries.

He was there for a whole host of kiddos and their families when he was the president of Dixie Youth Baseball, staying up late to close up concession stands and lock up equipment rooms, turn off the light or repairs the roofs of dugouts.

He was there for this individual kiddo when he needed to turn a block of pine into a 1958 Corvette to race against other Boy Scouts. And the time when I’d failed to sell enough Trails End popcorn to win some campfire starter tool, and he gave me one of his own fire-starter tools from the service. It didn’t look like the one in the catalog, but even then I knew it was better.

He was there in a deer stand hunting with me, which I tried to enjoy as much for him as to fit in with my friends, and when the uncontrollable chattering of my teeth wouldn’t sop, he asked me, “Do you want to stop making so much noise so that we might see a deer today.” He was also there on the driver’s side looking into the truck and up to me to find his keys locked inside and said, “What did you do?” I was 12. The answer was nothing; I’d done nothing.

He was there one morning in the last place I ever expected to see him: the University of Memphis campus. Walking to class one day, I saw a silhouette that seemed unmistakable. Surely it wasn't...?

It was him. Hadn’t even told me he’d be on campus, and we crossed paths purely by chance. We shared a quick meal, and when I’d finished finished class, I helped with the task that had brought him to campus. When we finished, he peeled off $50 for my work, and though I desperately needed it, I’d have been just as happy to do it for free.

He was there for me when I needed to move across the country, not once but twice, loading up a U-haul like a mix between a Tetris master and a museum curator and driving 23 hours.

He was there, anywhere, he could find his granddaughter, Delanie. There was no denying he was made to be a papaw.

And perhaps most amazingly, he was there, in an empty sanctuary as an answer to literal prayers. I was in high school and serving on a prayer committee for an ongoing revival. Our task was to pray for blessings during revival. I would go before school, arriving shortly after 7 a.m. During the course of my prayers, I started praying for him—for his soul, for his safety, for him in general. As I kneeled at the altar of the First Baptist Church in Selmer, I was startled by a voice. It was Dad, who’d unexpectedly been driving through town and had seen my car.

He would have been humbled by the crowd here today and the one that streamed through last night. And he would have been embarrassed because he hated being the center of attention.

But he’d want to you all to know how much it meant to him and how much he loved you right back.

And the worst part of it all is very simple—like the things he did so well, like this little speech.

Suddenly, too suddenly, he’s not there and won’t be again.

And the world is a poorer place for it.

Ten Worth Your Time

- I loved this short essay from the Yale Review from Alexander Chee. It’s about the moment he lost his father’s watch. It’s a beautiful piece of writing, but resonated for me because of the watch emphasis. My dad’s daily watch had become a Garmin Instinct, which I’d bought him for a Christmas gift a year or so before he passed. My mom gave it back to me and it was weeks before it left my wrist. I still wear it often, but I can’t imagine the feeling of losing it.

- A piece from The Hill that’s more interesting than well-written discusses something I’d somewhat forgotten about: the U.S. states commemorative quarters. My dad collected them, not in those little maps of the country with a slot for each state’s quarter, but in bulk. He wouldn’t have a Virginia quarter; he’d have 30-something of them. All states. He’d go to the bank on Fridays to deposit his check and while he was there, he’d ask for some of the new quarters. They’re probably still in various jars and bins at my mom’s house, right this very minute, because I bet the rest of the family forgot about them just like I did.

- The Masters concluded yesterday, and I’m not sure I would have ever cared if it weren’t for my dad. He taught me about golf. Introduced me to it. Despite a back injury that greatly reduced his willingness to play very often, it was probably the last hobby we shared together, and as such, I’ll probably never watch or play the game without a passing memory of him. Right now, Scottie Scheffler is the best in the game, and he’s got an unusual signature: wildly active feet in his swing. It’s a reminder that prowess (and even mere competence) can have varying looks and some may not conform to conventional wisdom about how it’s done. It’s especially true for golf, but no less true in any creative endeavor: Sometimes unconventional is beautiful. I think my dad would have liked the meteoric rise of Scottie the guy and would have been inspired by his quirky swing. How the ‘Scottie Shuffle’ is Scheffler’s unique weapon as he seeks a second Masters | The Athletic

- Solar farms. For a number of years, this was the number one no-go subject with my dad. Not because he was an oil man. Not because he was particularly against green energy. But 100% because a massive chunk of land behind his house that had once been farming fields was sold off to a company that put in a massive solar farm. Right behind the house. They were boxed in : the house fronted a state highway and all around the back there was now chainlink fence and massive solar panels and sheep to keep the grass and weeds at bay. It was (and is) an eyesore. It animated a persistent desire in what would be his final years to sell the house and move away. He wanted acres and acres of land, where a house could be in the middle of it and never again have a view taken away. It was his white whale; he was an obsessed Ahab. It was with this memory in mind that I read this High Country News piece about solar farms in the west and what it would really take to derive America’s power needs from the sun.

- My siblings and I bought my dad a 75-inch TV for a birth a few years ago. It was much to my chagrin that he spent so much time on it browsing Youtube videos, not watching any number of fantastic movies or TV shows. He was particularly fond of videos of restorations—didn’t really matter the object, but he loved watching old things being deconstructed, cleaned, lovingly restored and reassembled. But he watched all sorts of content, and it was with that in mind that I read this short piece from The Washington Post about how Youtube is the most consequential technology in America. And he for sure watched some terrible content and trained the algorithm to send him even more of it, and the article’s emphasis on Youtube’s influence reminded me of the podcast Rabbit Hole from The New York Times.

- Jay Caspian Kang wrote for The New Yorker on what phones are doing to our reading lives and whether there’s any going back. Relatedly, Platformer’s Zoë Schiffer wrote a sort of round-up of the ongoing debate around Jonathan Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation, the central argument of which was shared in an article for The Atlantic (and shared in this newsletter) about how smartphones are causing serious issues for teenagers.

- You know who else was skeptical of technology? The Unabomber. Not entirely sure why The Atlantic’s homepage section devoted to its massive archives circulated this piece from 2000 that explored whether Harvard University helped create the murderous recluse, but once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber

- Speaking of the archives, here’s a piece I enjoyed following the news of O.J. Simpson’s death: Ta-Nehisi Coates for The Atlantic. For a more contemporary take on his death, here’s Will Leitch in his newsletterthe and for New York magazine.

- A great podcast episode from ESPN Daily on the death of marathoner Kelvin Kiptum, one of the most accomplished marathoners ever who’d barely even started in his professional career. Today was the Boston Marathon, and it’s incredible to hear about Kiptum’s potential to have been the first marathoner to run a sub-2-hour marathon without all the assistance of the carefully coordinated effort that saw Eliud Kipchoge run the fastest recorded marathon that was not a world record.

- Last week marked the 30th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide. This piece from NPR tells the story of life since then, how Rwandans have moved on, how they remember, how they forgive. I revisited Philip Gourevitch’s incredible book We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families at the first of the year, and it remains a staggering account of what happened and marvelously written. Here’s a collection of dispatches that he wrote during the following 20 years for The New Yorker.

More From Me

Over on my blog, I’ve been writing about various topics of interest to me.

Two More For The Village Voice

Culture Diary

Here’s a collection of what I’ve been consuming in the past week.

The legend for my list was stolen from Steven Soderbergh, where ALL CAPS represents a movie, Sentence Case is a TV show, ALL CAPS ITALICS is a short film, Italics is a book, and bold is a live performance or show. A number in parentheses after a TV show highlights how many episodes I watched. An asterisk after an entry means it’s a rewatch. The source of the movie or show, whether streaming service, physical media, or in theaters, is shown in parentheses as well.